Below is Ann Coulter’s brilliant

synopsis of the past 150 years of American political history. It reads like a middle-school social studies essay; and if I were that particular middle-schooler’s teacher, I’d have given her a D minus. You might ask why not an F; I wouldn’t have failed her because, well, her spelling is just impeccable:

“In the history of the nation, there has never been a political party so ridiculous as today’s Democrats. It’s as if all the brain-damaged people in America got together and formed a voting bloc.

The Federalists drafted the greatest political philosophy ever written by man and created the first constitutional republic. The anti-Federalists—or ‘pre-Democrats,’ as I call them—were formed to oppose the Constitution, which, to a great extent, remains their position today.

Andrew Jackson, the father of the Democratic Party, may have had some unpalatable goals, but at least they were big ideas. Wipe out the Indians, kill off the national bank and institute a spoils system. Love him or hate him, he never said, ‘I’ll be announcing my platform sometime early next year.’ The Whigs were formed in opposition to everything Jackson stood for.

The Republican Party emerged from the Whigs when the Whigs waffled on slavery. (They were ‘pro-choice’ on slavery.) The Republican Party was founded expressly as the anti-slavery party, which to a great extent remains their position today.

Having won that one, today’s Republican Party stands for life, limited government and national defense. And today’s Democratic Party stands for ... the right of women to have unprotected sex with men they don’t especially like. We’re the Blacks-Aren’t-Property/Don’t-Kill-Babies party. They’re the Hook-Up party.”

In her attempt to revile the Democrats, Coulter does sloppy history. Or maybe she’s just dumb. In any event, she should watch what she says about the Anti-Federalists, because today’s conservative Republicans have far more in common with the Anti-Federalist tradition than Coulter seems to realize.

Moreover, her simplistic formula of “Republicans (winners) = Federalists; Democrats (losers) = Anti-Federalists” betrays her total ignorance of American political history and the evolution of our current political parties. Coulter’s equation does not stand up to even a basic historical analysis, which I will humbly attempt to offer here. She does what many social conservatives do; namely, she takes her view of current events and projects it backward onto history and imagines that things have always pretty much been the way they are now. Coulter must not have taken American Political History at either Cornell or the University of Michigan Law School. Either that or she slept through it. Perhaps the fur coat she frequently wore to class made her sleepy.

For starters, the Republicans are not now and have not historically been

consistent advocates of limited government. More importantly, it was the Anti-Federalists who stood for limited government, not the Federalists, with whom Coulter seems so eager to identify. I could stop there, because, frankly, I think I’ve already said enough to demonstrate the utter flimsiness of her analysis; but I’m not going to stop, because I think it’s important to set the record…ahem… straight.

The Democratic Party and the Republican Party, both of whom emerged during the middle half of the 19th century, married Federalist

and Anti-Federalist elements. I would argue that both parties borrowed from and simultaneously broke with their predecessors in some important ways, which I’ll explain. Moreover, since that time, both have undergone significant evolution (heck, they’ve undergone significant evolution in just the past several decades let alone the past century-and-a-half), and have, in many ways, strayed from their origins. Furthermore, the evolution of both parties must be understood in the context of the sectionalism (i.e. North versus South) and industrialization that were the dominant themes of 19th-century politics

and the new sectionalism (again, North versus South) that re-emerged a century later during the Civil Rights era; and let’s not forget the Reaganomics that followed during the 1980s.

So are today’s Democrats a mere mirror of 18th-century Anti-Federalism, while the Republicans are, like the original Federalists, the true defenders of the Constitution as Coulter suggests? To answer that question, we need to look back at things on the eve of the 19th century, when America was still a young republic. Back then, two factions had emerged; on one side were the Federalists who had argued for the ratification of the Constitution, while on the other were the Anti-Federalists, who, once the Constitution had been ratified, organized themselves under Thomas Jefferson’s leadership as the Democratic-Republicans (what a name!). They are sometimes referred to by historians as Jeffersonian Republicans, but were known by Americans of the late 18th and early 19th century simply as Republicans. Confused yet?

What did these Jeffersonian Republicans stand for? As the ideological heirs of the Anti-Federalists, they were the party of “strict constructionism” and limited government. The Republicans were also vehement proponents of “states rights,” which was a corollary of their strict constructionism, though their states rights position was not always consistent with a strict reading of the Constitution, as was the case during the

Nullification Crisis.

With the election of Jefferson to the presidency in 1801, the Republicans became the dominant political party and remained so for the next two decades. It was only natural as the governing party that they gradually began to adopt many of the “nationalizing” tenets of their former opponents, the Federalists. They supported, for example, the creation of the Second National Bank, a concept which had been anathema to early Anti-Federalists. However, the widening of suffrage during the Jacksonian era (1820s and 30s) saw a resurgence of the old Anti-Federalist program of limited government, strict constructionism, and states rights, especially as the sectional conflict over slavery began to heat up.

Still, the new Democratic Party that was formed between 1824 and 1834 was hardly a mere reincarnation of either the old Anti-Federalists (as Coulter suggests) or the Jeffersonian Republicans. For example, the Democrats were vehemently opposed to a centralized national bank, which the Jeffersonian Republicans had eventually come to support. Furthermore, the Democrats were not always faithful to their Anti-Federalist roots and sometimes supported the idea of a strong central government, especially when it came to supporting federal protectionism through tariffs (though this proved to be a divisive issue) and the protection of slavery and enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law (which proved to be an even more divisive issue).

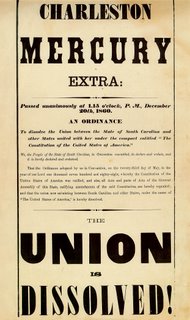

The point here is that the Democratic Party was fractured, largely along sectional lines, with Southern Democrats taking an increasingly strong states rights position in defense of slavery and its expansion into new territories, but favoring federal authority when it came to protecting slavery where it existed and demanding the return of runaway slaves by federal marshals. By the mid-1850s as the sectional crisis began to worsen, many Northerners had begun to join the ranks of the newly formed Republican Party, and with their support, Abraham Lincoln won the election of 1860.

Similarly, it would be a mistake to conclude that the Republican Party was nothing more than the Federalists reborn. While it is true that the Republicans incorporated old Whig elements who were themselves the heirs of the Federalist tradition (Coulter sort of gets this part right), it was not long before they began to jettison some of their strict Federalist positions. For one thing, the industrialization that took place during the latter half of the 19th century insured the continued evolution of political thought and its embodiment in the two dominant political parties.

Furthermore, industrialization in the North meant that the Republicans gradually began to abandon their Federalist roots in favor of the old Anti-Federalist doctrines of limited government, especially when it came to the federal regulation of industry (notwithstanding either the Republican Party’s unwavering support for protectionist tariffs throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries or the emergence of Progressive Republicans such as “trust-buster” Theodore Roosevelt). The Republicans quickly learned that

laissez-faire economics and Federalism do not make good bedfellows. Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton had always know this. Ann Coulter apparently does not.

The Republican critique of Federalism continued during the latter half of the 20th century with the emergence of what would come to be known as “Reaganomics,” with its defense of a market economy free from the kinds of state interference that had characterized the New Deal. However, the Republican Party’s gradual embrace of Anti-Federalism would not be complete until the opposition of Southern Democrats toward the notion of a strong central government proved strong enough to overcome their revulsion to the party of Lincoln. This had begun during the Civil Rights era when successive Democratic administrations using federal authority forcibly imposed desegregation on the Jim Crow South. By the 1980s, Southerners began joining the ranks of the Republicans

en masse and when they joined, they brought in their traditional Anti-Federalism with them.

Since that time, strict constructionism itself has undergone significant evolution. Originally meant as a principle of strictly interpreting the Constitution to limit the powers of the federal government so as to protect states rights, strict constructionism has since mutated into an ideology of executive imperialism and a strict interpretation of the Constitution to dismantle the economic and welfare programs of the New Deal and undermine the rights of individuals, especially minority groups seeking equal protection.

In reality, today’s Republican Party combines the Anti-Federalism of

laissez-faire economics with a new version of the Anti-Federalist notion of strict constructionism, which seeks to

limit federal authority when it comes to funding social programs and interfering with industry, while simultaneously

expanding federal authority when it comes to interfering with the lives of individuals.

One of the leading Federalists of his day, Alexander Hamilton argued against

laissez-faire economics and expressly rejected Adam Smith’s

Wealth of Nations with its defense of unregulated capitalism and its critique of state-imposed economic controls. Furthermore, the notion of judicial review—the recent exercise of which has brought accusations of judicial activism and judicial tyranny—was originally a Federalist concept, largely articulated by Hamilton himself. In

Federalist No. 78, Hamilton argued that the judiciary

“in a republic it is a no less excellent barrier to the encroachments and oppressions of the representative body. And it is the best expedient which can be devised in any government, to secure a steady, upright, and impartial administration of the laws.

Some perplexity respecting the rights of the courts to pronounce legislative acts void, because contrary to the Constitution, has arisen from an imagination that the doctrine would imply a superiority of the judiciary to the legislative power. It is urged that the authority which can declare the acts of another void, must necessarily be superior to the one whose acts may be declared void.

The interpretation of the laws is the proper and peculiar province of the courts. A constitution is, in fact, and must be regarded by the judges, as a fundamental law. It therefore belongs to them to ascertain its meaning, as well as the meaning of any particular act proceeding from the legislative body. If there should happen to be an irreconcilable variance between the two, that which has the superior obligation and validity ought, of course, to be preferred; or, in other words, the Constitution ought to be preferred to the statute, the intention of the people to the intention of their agents.

Nor does this conclusion by any means suppose a superiority of the judicial to the legislative power. It only supposes that the power of the people is superior to both; and that where the will of the legislature, declared in its statutes, stands in opposition to that of the people, declared in the Constitution, the judges ought to be governed by the latter rather than the former. They ought to regulate their decisions by the fundamental laws, rather than by those which are not fundamental.”

I cannot imagine that these words would sit well with today’s conservative Republicans. That’s not surprising, since most bigots don’t like it when the courts declare discriminatory laws to be unconstitutional.

These two ideas—the notion that the state should regulate the economy and the importance of a strong judiciary—the very positions for which liberal Democrats have been roundly criticized, even vilified, by conservatives like Coulter are positions that the Federalists would have understood and defended. But I don’t expect Coulter to admit how much liberal Democrats have in common with the original Federalists.

Coulter likens the Democrats to the Anti-Federalists for one reason only. She is trying to discredit them by connecting them with the party that, two-and-a-quarter centuries ago, opposed the ratification of the Constitution. What she clearly misses, however, is that today’s Republican Party actually has a lot in common with the Anti-Federalist tradition (of course, the real heirs of the Anti-Federalists are the wacko militias out in the mid-West who want to do away with the federal government altogether). The philosophies of both parties today contain disparate elements that could be considered both Federalist and Anti-Federalist, just as they did when they were founded a century-and-a-half ago.

One could say far worse things about the Republican Party than suggesting that they are like the Anti-Federalists, because in reality, there is nothing wrong with the notion of limited government. It’s a good notion. We certainly need a less intrusive federal government these days. The problem is that conservative Republicans only invoke that doctrine when it suits them. They want a smaller federal government when it comes to lower taxes and

laissez-faire economics, but then turn around and argue for a massive federal defense budget, an imperial presidency, and a federal definition of marriage. That’s not very consistent with their Anti-Federalist leanings. But then again, conservatives have never been very good at the whole history thing.