Pierced

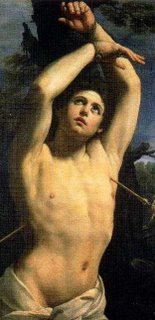

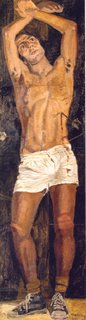

Sometimes a delicate waif; at other times, a muscular youth—however he’s portrayed, nobody evokes medieval and Renaissance homoeroticism quite like Saint Sebastian.

Sometimes a delicate waif; at other times, a muscular youth—however he’s portrayed, nobody evokes medieval and Renaissance homoeroticism quite like Saint Sebastian.A member of the praetorian guard who was also a crypto-Christian convert, he was shot full of arrows for his illicit devotion to Christ. He was later canonized by the Church, and his popularity as a subject for male artists who were, of course, on the official payroll demonstrates how in the midst of officially sanctioned homophobia,

there arose an illicit devotion to the beauty of the male form and a climate that was hospitable to such imagery. Just as Saint Sebastian was executed because for a Roman soldier to profess loyalty to Christ was considered high treason, the many homoerotic and subversive images of Saint Sebastian reveal centuries of treason within the ranks of the Church. Then as now, homosexuality somehow managed to survive within an environment that was, at least on the surface, openly hostile to same-sex love. However, then as now, the pressure of the closet produced a repressed and tortured sexuality, just as Saint Sebastian is, in the many works portraying him, literally repressed and tortured.

there arose an illicit devotion to the beauty of the male form and a climate that was hospitable to such imagery. Just as Saint Sebastian was executed because for a Roman soldier to profess loyalty to Christ was considered high treason, the many homoerotic and subversive images of Saint Sebastian reveal centuries of treason within the ranks of the Church. Then as now, homosexuality somehow managed to survive within an environment that was, at least on the surface, openly hostile to same-sex love. However, then as now, the pressure of the closet produced a repressed and tortured sexuality, just as Saint Sebastian is, in the many works portraying him, literally repressed and tortured. In the iconography of Saint Sebastian, religious ecstasy and sexual ecstasy are merged. As the arrows pierce his flesh, he swoons almost trancelike, as does the viewer who gazes upon his semi-nude body. Surely, he inspired countless masturbatory fantasies (and probably not a few sadomasochistic ones) among both priest and peasant, and especially among the monks whose cloisters were adorned with his image.

In the iconography of Saint Sebastian, religious ecstasy and sexual ecstasy are merged. As the arrows pierce his flesh, he swoons almost trancelike, as does the viewer who gazes upon his semi-nude body. Surely, he inspired countless masturbatory fantasies (and probably not a few sadomasochistic ones) among both priest and peasant, and especially among the monks whose cloisters were adorned with his image. Saint Sebastian remains a poster boy for idealized male beauty. However, while he was one of Europe’s most renowned sex symbols, he was and is an arresting symbol of intolerance and persecution. He may look like the object of our desire—and not just ours, but the desires of the artists who produced the images, the patrons who paid for them, and the churchgoers who reverenced them—but we cannot escape the fact that in those same images, he is also an object of wrath. Saint Sebastian is, above all, a victim and a martyr. He remains for us a most powerful symbol of all those who have suffered violence at the hands of a repressive regime and of the Church’s ongoing crusade against manifestations of same-sex love.

Saint Sebastian remains a poster boy for idealized male beauty. However, while he was one of Europe’s most renowned sex symbols, he was and is an arresting symbol of intolerance and persecution. He may look like the object of our desire—and not just ours, but the desires of the artists who produced the images, the patrons who paid for them, and the churchgoers who reverenced them—but we cannot escape the fact that in those same images, he is also an object of wrath. Saint Sebastian is, above all, a victim and a martyr. He remains for us a most powerful symbol of all those who have suffered violence at the hands of a repressive regime and of the Church’s ongoing crusade against manifestations of same-sex love.A note on the images:

The first image is a tantalizing detail from Giovanni de Lutero's (1479-1542) Saint Sebastian (oil on panel, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan); the second, from Antonello da Messina's (1430-1479) Saint Sebastian (1476, tavola, Staatliche Gemäldegalerie, Berlin); the third is Guido Reni’s (1575-1642) version of the saint (1615-1616, oil on canvas, Palazzo Rosso, Genoa). Lastly, a modern treatment by Yiannis Tsarouchis (1910-1989).

1 Comments:

http://celsius32.blogspot.com

Tassos , poly wraio to site sou , myrizei evgenikh Ellada , afth pou dyskola vriskeis shmera isws sth xwra apo tous ithageneis :)

Post a Comment

<< Home