Nudes and Pubes I

After a heated email exchange with my friend Kate (during which we almost came to cyber-blows) as a result of a statement I made in a previous post about the rarity of pubic hair in art prior to the 20th century, I finally asked her to do a guest post giving an alternative point of view. I’m kidding; there was no heated exchange nor were there any cyber-blows. Kate simply pointed out that she was pretty sure she had come across examples of pubes in art (in both painting and sculpture), which fascinated (and titillated) me, so I eagerly asked her to share her knowledge of artistic pubes. Kate was trained as an art historian and is one of the brightest people I know. I have lots to learn from her in the realm of art history (and not just where pubes are concerned). Thanks, Kate!

Nudes & Pubes I

by Kate

Dean resurrected my inner art historian when he made the assumption that it is rare to see a nude with pubic hair prior to the 20th century. I felt challenged. I know I visually encountered curly and wiry tufts while studying for art history finals in the darkened slide library of my alma mater. Ditching my required reading for tonight’s class, I immediately shelved my book on linguistic phrase structure and morphological rules to explore depictions of pubic hair in European art prior to the 20th century. I found it ironic that while many of us spend most of our lives trying to rid pubic hair from our bodies and bathtubs, I spent an afternoon searching for pubes in the virtual galleries of the world’s greatest museums. What a lovely way to spend a snowy afternoon. After a fruitless (and hairless) search in Vassari’s Lives of the Artists, I realized Dean indeed dropped quite a challenge. This project could take months to compile, so I have decided to post some good examples as I discover them.

Dean resurrected my inner art historian when he made the assumption that it is rare to see a nude with pubic hair prior to the 20th century. I felt challenged. I know I visually encountered curly and wiry tufts while studying for art history finals in the darkened slide library of my alma mater. Ditching my required reading for tonight’s class, I immediately shelved my book on linguistic phrase structure and morphological rules to explore depictions of pubic hair in European art prior to the 20th century. I found it ironic that while many of us spend most of our lives trying to rid pubic hair from our bodies and bathtubs, I spent an afternoon searching for pubes in the virtual galleries of the world’s greatest museums. What a lovely way to spend a snowy afternoon. After a fruitless (and hairless) search in Vassari’s Lives of the Artists, I realized Dean indeed dropped quite a challenge. This project could take months to compile, so I have decided to post some good examples as I discover them.

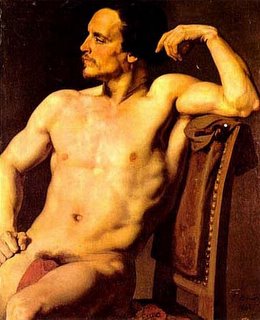

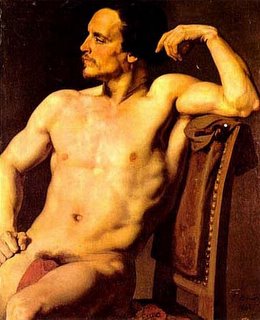

The example du jour is Paul Baudry’s The Wrestler Meissonier (1848, oil on canvas). Baudry (1828-1886) was considered to be a second-rate artist of the Academic Classicism School, though he did manage to win the coveted Prix de Rome. In the course of his residence in Italy, Baudry derived strong inspiration from Italian art and the mannerism of Correggio (Antonio Allegri, c. 1489-1534). Correggio’s masterpiece is arguably Venus, Satyr, and Cupid (previously known as Jupiter and Antiope, circa 1523-25, oil on canvas, Musée du Louvre, Paris). Just one look at Correggio’s Venus reveals her in her full and natural glory. The work was described in the 17th century as a “Venerie mundano” or, in Neoplatonic terms, “earthly Venus”—referring to carnal love and the pleasures of the flesh. Correggio was too technically skilled to leave the viewer to question the darkened nether zone as a careless shadow from a mysterious light source. What we notice are the soft tufts of a Venus who had not gone Brazilian! Perhaps this Renaissance masterpiece emboldened Baudry to portray his wrestler revealing his own earthly elements (or tufts). Please don’t ask about the red sock.

The example du jour is Paul Baudry’s The Wrestler Meissonier (1848, oil on canvas). Baudry (1828-1886) was considered to be a second-rate artist of the Academic Classicism School, though he did manage to win the coveted Prix de Rome. In the course of his residence in Italy, Baudry derived strong inspiration from Italian art and the mannerism of Correggio (Antonio Allegri, c. 1489-1534). Correggio’s masterpiece is arguably Venus, Satyr, and Cupid (previously known as Jupiter and Antiope, circa 1523-25, oil on canvas, Musée du Louvre, Paris). Just one look at Correggio’s Venus reveals her in her full and natural glory. The work was described in the 17th century as a “Venerie mundano” or, in Neoplatonic terms, “earthly Venus”—referring to carnal love and the pleasures of the flesh. Correggio was too technically skilled to leave the viewer to question the darkened nether zone as a careless shadow from a mysterious light source. What we notice are the soft tufts of a Venus who had not gone Brazilian! Perhaps this Renaissance masterpiece emboldened Baudry to portray his wrestler revealing his own earthly elements (or tufts). Please don’t ask about the red sock.

Nudes & Pubes I

by Kate

Dean resurrected my inner art historian when he made the assumption that it is rare to see a nude with pubic hair prior to the 20th century. I felt challenged. I know I visually encountered curly and wiry tufts while studying for art history finals in the darkened slide library of my alma mater. Ditching my required reading for tonight’s class, I immediately shelved my book on linguistic phrase structure and morphological rules to explore depictions of pubic hair in European art prior to the 20th century. I found it ironic that while many of us spend most of our lives trying to rid pubic hair from our bodies and bathtubs, I spent an afternoon searching for pubes in the virtual galleries of the world’s greatest museums. What a lovely way to spend a snowy afternoon. After a fruitless (and hairless) search in Vassari’s Lives of the Artists, I realized Dean indeed dropped quite a challenge. This project could take months to compile, so I have decided to post some good examples as I discover them.

Dean resurrected my inner art historian when he made the assumption that it is rare to see a nude with pubic hair prior to the 20th century. I felt challenged. I know I visually encountered curly and wiry tufts while studying for art history finals in the darkened slide library of my alma mater. Ditching my required reading for tonight’s class, I immediately shelved my book on linguistic phrase structure and morphological rules to explore depictions of pubic hair in European art prior to the 20th century. I found it ironic that while many of us spend most of our lives trying to rid pubic hair from our bodies and bathtubs, I spent an afternoon searching for pubes in the virtual galleries of the world’s greatest museums. What a lovely way to spend a snowy afternoon. After a fruitless (and hairless) search in Vassari’s Lives of the Artists, I realized Dean indeed dropped quite a challenge. This project could take months to compile, so I have decided to post some good examples as I discover them.  The example du jour is Paul Baudry’s The Wrestler Meissonier (1848, oil on canvas). Baudry (1828-1886) was considered to be a second-rate artist of the Academic Classicism School, though he did manage to win the coveted Prix de Rome. In the course of his residence in Italy, Baudry derived strong inspiration from Italian art and the mannerism of Correggio (Antonio Allegri, c. 1489-1534). Correggio’s masterpiece is arguably Venus, Satyr, and Cupid (previously known as Jupiter and Antiope, circa 1523-25, oil on canvas, Musée du Louvre, Paris). Just one look at Correggio’s Venus reveals her in her full and natural glory. The work was described in the 17th century as a “Venerie mundano” or, in Neoplatonic terms, “earthly Venus”—referring to carnal love and the pleasures of the flesh. Correggio was too technically skilled to leave the viewer to question the darkened nether zone as a careless shadow from a mysterious light source. What we notice are the soft tufts of a Venus who had not gone Brazilian! Perhaps this Renaissance masterpiece emboldened Baudry to portray his wrestler revealing his own earthly elements (or tufts). Please don’t ask about the red sock.

The example du jour is Paul Baudry’s The Wrestler Meissonier (1848, oil on canvas). Baudry (1828-1886) was considered to be a second-rate artist of the Academic Classicism School, though he did manage to win the coveted Prix de Rome. In the course of his residence in Italy, Baudry derived strong inspiration from Italian art and the mannerism of Correggio (Antonio Allegri, c. 1489-1534). Correggio’s masterpiece is arguably Venus, Satyr, and Cupid (previously known as Jupiter and Antiope, circa 1523-25, oil on canvas, Musée du Louvre, Paris). Just one look at Correggio’s Venus reveals her in her full and natural glory. The work was described in the 17th century as a “Venerie mundano” or, in Neoplatonic terms, “earthly Venus”—referring to carnal love and the pleasures of the flesh. Correggio was too technically skilled to leave the viewer to question the darkened nether zone as a careless shadow from a mysterious light source. What we notice are the soft tufts of a Venus who had not gone Brazilian! Perhaps this Renaissance masterpiece emboldened Baudry to portray his wrestler revealing his own earthly elements (or tufts). Please don’t ask about the red sock.

2 Comments:

hmmmm... i think that the correggio is a bit of a stretch. i think it's more shadow than pubes going on there, but, admittedly, i do know less about the female, er, anatomy.

now the wrestler... can i say how much i love him? but baudry, man, why show pubes and not his cock? what's up with that? and all i have to say about the red sock is "go sox!" :)

Pube-er-ific!

And you KNOW I'm going to be on a quest all semester in my current art history class, now. LOL!

Post a Comment

<< Home