Captain Christmas

The Liberty Counsel’s “Friend or Foe Christmas Campaign,” which began in 2003, has found a bold new spokesman in the person of Captain Christmas himself (a.k.a. Jerry Falwell), who challenged the City of Boston’s rather silly decision to designate the Christmas tree on Boston Common a “holiday tree” (They’ve since gone back to calling it a Christmas tree). Falwell and his minions claim that the Christmas tree is essentially a Christian symbol. One could more persuasively claim the Christmas tree as a pre-Christian symbol of fertility, a phallic symbol to be precise, but that’s a whole other story.

The Liberty Counsel’s “Friend or Foe Christmas Campaign,” which began in 2003, has found a bold new spokesman in the person of Captain Christmas himself (a.k.a. Jerry Falwell), who challenged the City of Boston’s rather silly decision to designate the Christmas tree on Boston Common a “holiday tree” (They’ve since gone back to calling it a Christmas tree). Falwell and his minions claim that the Christmas tree is essentially a Christian symbol. One could more persuasively claim the Christmas tree as a pre-Christian symbol of fertility, a phallic symbol to be precise, but that’s a whole other story.The Bay State’s Puritan forebears would be turning over in their graves at the sight of a Christmas tree on Boston Common, whatever it’s called. Boston’s founders were children of the Reformation and adhered to a rather strict interpretation of the Bible, as does Falwell himself, or so he claims. Perhaps he’s a liberal in disguise! There is no doubt that those whom Falwell and the evangelicals claim as their spiritual ancestors would have frowned—no, they would have scowled—upon the mere suggestion that the frivolous decorating of an evergreen or even Christmas itself has anything to do with Christianity. The Puritans and other Reformation-era sects regarded the celebration of Christmas—and other feastdays—as an example of “popery,” their preferred term for Catholicism, which they believed had become infected with heathen and idolatrous elements.

I disapprove of Captain Christmas not because I think that “holiday tree” is a better name or because I want to reassert the pre-Christian meaning of the Christmas tree, but because the Liberty Counsel’s campaign is part of its larger agenda to undermine pluralism and foist on America a Christian hegemony. In our post-Christian world, moreover, it seems to me that the Christmas tree is neither a Christian nor a pre-Christian symbol any longer. Above all, it symbolizes syncretism, a concept with which Captain Christmas appears to be unfamiliar.

Syncretism is the process by which disparate religious beliefs and practices are blended together. For example, a newer religion may incorporate (or become infiltrated by) elements of an older, more established religion. Forbidden religions may also take on the guise of an approved religion as a survival mechanism. Sometimes it is simply a matter of deeply-rooted folk practices adapting themselves to or influencing the prevailing orthodoxy.

For millennia the evergreen (duh, because it is green throughout the year) was a potent symbol of immortality and regeneration. It is no surprise that the medieval folk practice of decorating evergreens got incorporated into the Christian feast of the nativity. Christmas itself is a blending of the nativity story and the ancient Roman festival of Sol Invictus, the rebirth of the sun following the winter solstice. In this way, the Christmas tree is an example of syncretism (as is Christmas itself); but the tree is also a symbol of a much larger syncretism that lies close to the heart of organized Christianity.

Decorating evergreens, the very symbol of immortality, has been a part of Christmas since at least the sixteenth century. The Christmas tree has become inextricably tied to the official commemoration of Christ's birth. However, while for some it might symbolize the birth of Christ as a historical event, what I am talking about is not the birth of Christ the person, but the birth—the creation—of Christ the construction. The Christmas tree symbolizes the reinvention of Christ and a shift away from the Jewish peasant who became a radical, egalitarian, anti-authoritarian advocate of the poor and marginalized in 1st-century Roman-occupied Palestine. This Christ had limited appeal (see “The Rich Young Man” episode in Mark 10:17-22 and Matthew 19:16-22). The tree represents the birth of a new Christ, the resurrected Son of God—not the person, but the myth that was created to spread the new religion. The Christmas tree is Christ newly adorned with decorative immortality. It symbolizes Christ romanticized, mythologized, and reinvented.

Decorating evergreens, the very symbol of immortality, has been a part of Christmas since at least the sixteenth century. The Christmas tree has become inextricably tied to the official commemoration of Christ's birth. However, while for some it might symbolize the birth of Christ as a historical event, what I am talking about is not the birth of Christ the person, but the birth—the creation—of Christ the construction. The Christmas tree symbolizes the reinvention of Christ and a shift away from the Jewish peasant who became a radical, egalitarian, anti-authoritarian advocate of the poor and marginalized in 1st-century Roman-occupied Palestine. This Christ had limited appeal (see “The Rich Young Man” episode in Mark 10:17-22 and Matthew 19:16-22). The tree represents the birth of a new Christ, the resurrected Son of God—not the person, but the myth that was created to spread the new religion. The Christmas tree is Christ newly adorned with decorative immortality. It symbolizes Christ romanticized, mythologized, and reinvented. For me, the Christmas tree is a metaphor for the way in which the early Church co-opted the very notion of resurrection itself, an idea with which the Greco-Roman world had great affinity. One need look no further than the mystery religions of Osiris-Horus and Bacchus/Dionysos, both of which contained a resurrection myth. Interestingly, Dionysos was sometimes referred to as Διόνυσος Δενδριτής, meaning “Dionysos of the Trees.” The resurrected Christ caught on in a way that the peasant Christ never could have. A new Christ had to be born. It is this birth that the Christmas tree symbolizes. If Captain Christmas is uncomfortable with this symbolism because it recognizes Christianity’s syncretic past, I’d like to remind him that if it hadn't been for the absorption of pagan elements, Christianity would not have survived at all.

For me, the Christmas tree is a metaphor for the way in which the early Church co-opted the very notion of resurrection itself, an idea with which the Greco-Roman world had great affinity. One need look no further than the mystery religions of Osiris-Horus and Bacchus/Dionysos, both of which contained a resurrection myth. Interestingly, Dionysos was sometimes referred to as Διόνυσος Δενδριτής, meaning “Dionysos of the Trees.” The resurrected Christ caught on in a way that the peasant Christ never could have. A new Christ had to be born. It is this birth that the Christmas tree symbolizes. If Captain Christmas is uncomfortable with this symbolism because it recognizes Christianity’s syncretic past, I’d like to remind him that if it hadn't been for the absorption of pagan elements, Christianity would not have survived at all.You might ask why I would want to celebrate that. I don’t really. The birth of organized Christianity’s Christ is just one of the Christmas tree’s many layers of meaning. When Joe (my partner) and I decorate our tree, we are creating a symbol of yet another kind, one that is neither Christian nor pre-Christian. We are creating a symbol of inversion.

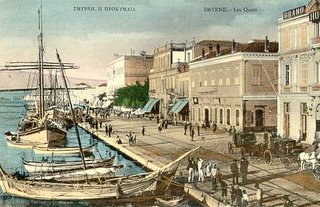

The idea of bringing nature indoors, turning the inside into the outside, is one that the pre-Christian world certainly would have recognized. Nor was the ancient world a stranger to ritualized inversion. In fact, many cultures throughout the Mediterranean still practice ritualized inversion as part of certain holidays—men dressing as women, women and men engaging in a kind of gender role reversal for the day. However, while it may look like Joe and I are reviving an old pagan custom, what we are really doing is creating a symbol of our own queerness, because queerness and inversion, while by no means synonymous, are intimately related. For us, the Christmas tree isn’t so much about immortality or the winter solstice. The Christmas tree, like us, is queer. It turns things upside down and inside out. I can only imagine what Captain Christmas and his evangelical elves would say about that.

A note on the images:

The top image is Ashurbanipal and the Sacred Tree (bas relief, British Museum, London). Ashurbanipal ruled the Assyrian Empire from 668 to 627 BCE. Could this be the very first Christmas tree?

The depiction of the resurrection is the middle panel of Hans Memling’s (1430-1494) Resurrection Triptych (oil on panel, Musée du Louvre, Paris). Are those Christmas trees the angels are waving?

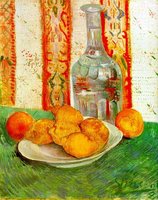

Lastly, I’ve included Caravaggio’s (1571-1610) Bacchus (c.1596, oil on canvas, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence), though this could easily be mistaken for a young Jesus or, better yet, a young Father Christmas.