An anonymous comment left in response to

this post caught my attention, and I felt it deserved more than simply a comment in reply. Therefore, I’ve put together a more detailed response, which I hope someone will find useful.

Anonymous said...

I’d like to hear more about what you think the Bible does condemn about homosexuality, because I don’t think it condemns an entire group of people who are gay and lesbian. I think it condemns prostitution and idolatry. But the same sex practices of that age aren’t anything close to what homosexual love and relationship can be like today.

Check out Temple Gray’s book, Gay Unions. He speaks of what sexuality was like in the ancient world. Nothing like what we have today in the heterosexual or homosexual sense of what is possible now. FHT

First of all, thank you for the question. I think it’s an important one, and I’m happy to explain my position more fully. I believe that as far as the Bible (or any sacred text) is concerned, I think one should begin by asking two basic questions. The first is, “What does the text say?” and the second is “Is the text authoritative and binding on me?” The first question is hermeneutical in nature, while the second is more theological. They are both equally important. Often, these questions are not asked separately, or the authority of the text is simply taken for granted. I think that if a person approaches the Bible as if it were authoritative and all its proscriptions universally binding, then it is difficult to give an honest and objective reading of the text. The stakes are too high.

It seems to me that if one is unable (because of convictions, upbringing, etc.) to dismiss the authority of the text, that person is then compelled to neutralize particularly troublesome passages by coming up with interpretations that are non-threatening and that affirm his or her identity, especially if that person feels s/he cannot change.

On the other hand, one can neutralize the authority of the text itself, as I have done. I consider the Bible no more sacred than any other religious group’s text. In other words, I afford the Bible no more authority than any other group’s sacred text. As a result, I can offer an honest critique of the Biblical texts and embrace an interpretation even when it conflicts with who I am, the way I live, and what I think.

Of course, I’m not saying that the authority of the Bible (or any other sacred text) is to be treated lightly. I have wrestled with this question for many years. It was only after much soul searching and study that I have come to the conclusion that the Bible is not vested with any divine authority.

So, having established that I do not consider the Bible as authoritative or binding on me, I can consider the meaning of the passages that have historically been used to condemn homosexuality (i.e. Genesis 19, Leviticus 18:22, Romans 1:26-27, 1 Corinthians 6:9, 1 Timothy 1:10). I won’t attempt to offer a full exegesis of the individual passages themselves, because that would take far too long and it would bore far too many readers. Instead, I will speak in broader terms, focusing less on the particular acts or situations the passages themselves refer to, than on whether the proscriptions pertaining to homosexual acts were more akin to blanket proscriptions to be applied broadly or, conversely, were more limited in their scope.

Admittedly, it is not obvious what exactly is being condemned in those pesky passages.

Anonymous rightly points out that the homosexuality that we practice today is not the same as what existed back then. We must not project either our contemporary understanding of sexual identity or our particular categories and constructs of sexuality onto the ancient world. After all, to do so would be anachronistic and inaccurate. However, just because homosexuality in its current form(s) did not exist back then, it does not follow that what is being addressed in the various aforementioned Biblical passages has absolutely no connection to that which exists today.

If, for example, it is a particular sexual act that is being condemned without any qualification

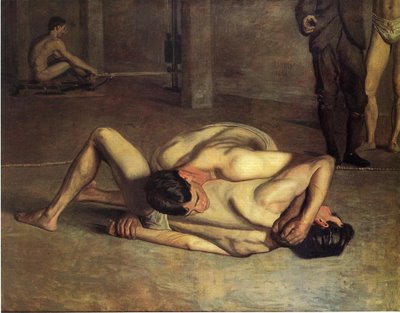

whatsoever, the original context in which the condemnation was issued becomes less relevant, especially if that same sexual act (like two men fucking) continues to be performed today, regardless of the particular cultural context in which that act occurs. Many queer Christians look at the context in which the condemnation was issued as the qualifier itself, but I think that imposes a limitation on the proscription that would have struck the original writers as quite odd.

In other words, many queer Christians become preoccupied with

why the proscriptions were issued and the particular situation (or abuse) that they were meant to address, as if to demonstrate that if we avoid the particulars of that situation (by not becoming a temple prostitute), somehow the proscription doesn’t apply to us and we’re just fine. However, I myself am not sure that the applicability of those passages was meant to be limited in such a fashion. After all, wouldn’t it be foolish to argue that 1 Corinthians 6:9 was meant to apply only to Corinthian Christians, but not Christians in Ephesus? If I’m going to conclude that those passages don’t apply to me, it’s because I reject the Bible’s authority, and not because I think that what I do in the bedroom isn’t addressed in those passages, because it probably is.

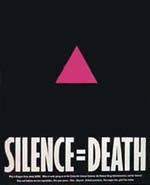

This might seem to many like a dangerous concession to the Religious Right, who love to use those passages to justify legislation that marginalizes GLBT people. However, given my unorthodox and iconoclastic take on scriptural authority (i.e. there is none), I’m not too worried about how I interpret certain Biblical passages. I’m not going to pretend that the Bible is 100% gay-friendly for political reasons. Besides, in combating the fanaticism of the Religious Right, I would much rather focus on constitutional questions than theological questions. After all, what the Bible says is ultimately irrelevant in a discussion of GLBT civil rights in America.

Getting back to the subject at hand, I admit that it is quite possible that the various Biblical proscriptions of homosexual acts arose in response to something very specific. That does not mean, however, that the proscriptions were meant to be narrowly interpreted or applied. Even if Leviticus 18:22 was formulated in response to male temple prostitution among the nations whom the Israelites felt it was their destiny to dispossess and annihilate, that does not mean that other forms of same-sex activity were considered acceptable as long as they did not consist of prostitution or gender-bending as was often the case in the cultic practices of the ancient Near East. To me, Leviticus 18:22 reads as a broad-based proscription. I do not believe it was meant to be limited in its scope.

I think it is even harder to make an argument about the limited nature of the New Testament proscriptions. Homosexual practices and relationships were, I imagine, much more diverse in the Greco-Roman era than in the Bronze Age. Nor was homosexuality in the Greco-Roman world limited to the practice of pederasty, which was the socially accepted form that it took in classical Greece. In the first century CE, an educated and Hellenized Jew of the Diaspora like Saul of Tarsus (Paul) would have been exposed to homosexuality in different forms, from pederasty and temple prostitution to marriage-like relationships between same-sex partners of roughly the same age (see Craig A. Williams’

Roman Homosexuality).

As a result, it is once again difficult for me to understand precisely what Paul is referring to in Romans 1:26-27. Likewise, in 1 Corinthians 6:9 and 1 Timothy 1:10, the writer uses what many consider to be a neologism, αρσενοκοίταις, a word that has been rendered as “homosexuals” by contemporary translators (and “sodomites” by previous generations of translators). It literally means “manfuckers,” and while Paul might have been reacting to the orgiastic homosexual practices that took place at Corinth, there is no evidence that he meant his condemnation to be limited in its scope.

It is almost as if people like my anonymous commentator believe that Moses and Paul never meant for their condemnations to be applied to loving, monogamous, and committed gay and lesbian couples. It’s as if s/he is saying that had Moses and Paul only known of such couples, they would surely have qualified their proscriptions. I don’t think that is the case at all.

The reality is that neither Moses nor Paul (or whoever composed the parts of the Bible normally attributed to them) was big on recreational sex of any kind. Sex, in ancient Israel, was for procreation; its very existence as a nation depended on procreation. It is not difficult to understand why homosexuality was condemned. Paul, on the other hand, is anti-sex. Period. Paul is not an advocate of either recreational or procreative sex. Sex, for Paul, belongs to the realm of

this world, which is passing away. The “family values” message of the Religious Right would have seemed very foreign to Paul, though less so to some of the post-Pauline writers of the New Testament who were moving toward an acceptance of the established order of patriarchy and the Roman

paterfamilias.

In spite of all that I have just said, I think it is important to recognize that it is indeed possible to give a queer-friendly reading of the Bible, as Theodore Jennings has done in

The Man Jesus Loved. However, the beauty of Jennings’s reading of the Bible is that he doesn’t engage in any hermeneutical gymnastics to dismiss the Bible’s critique of homosexuality. He acknowledges it and treats it as tragic evidence of the way in which the early Christian community very quickly lost its way. The critique of homosexuality evident in the New Testament is part of the tension between inclusivity and egalitarianism on one hand and patriarchy, the Law, and inequality on the other—a tension with which the early Christian community consistently wrestled. In the end, the New Testament’s proscriptions against homosexuality were a casualty in the Culture Wars of that era, just as anti-gay legislation is a frequent casualty in our own Culture Wars.

There are so many losers in the world. Thank the gods that there’s no shortage of pianos.

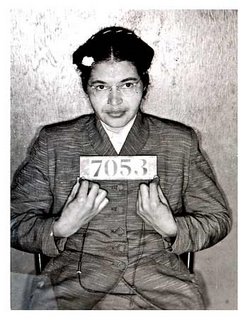

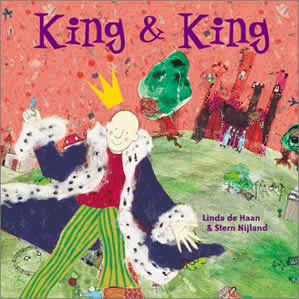

There are so many losers in the world. Thank the gods that there’s no shortage of pianos.  It seems that the Parkers and Wirthlins, whom the lawsuit identifies as devout Christians, objected to a second grade teacher’s classroom reading of King & King, which tells the story of two princes who fall in love with one another and get married. You’ll all remember Parker, who was jailed last year for refusing to leave school property when officials declined to exclude his 6-year-old son from a discussion of gay parents. Parker complained after his son brought home a “diversity book bag” with a book that depicted a gay family.

It seems that the Parkers and Wirthlins, whom the lawsuit identifies as devout Christians, objected to a second grade teacher’s classroom reading of King & King, which tells the story of two princes who fall in love with one another and get married. You’ll all remember Parker, who was jailed last year for refusing to leave school property when officials declined to exclude his 6-year-old son from a discussion of gay parents. Parker complained after his son brought home a “diversity book bag” with a book that depicted a gay family.