Catching up

I’m completely exhausted, and that’s having skipped Pride this past weekend because of the rain. I can’t imagine how tired I’d be right now had we been downtown on Saturday. As it is, it seems like we’ve been going non-stop since last Thursday.

Thursday night Joe, Mike the drummer, and I played at Café Apollonia. Thursday are normally Joe’s and Mike’s gig, but because we were all heading to a concert later that evening, it was easier for me to come along than have Joe pick me up at home afterwards. I didn’t play sandouri, just spoons and zils. We’d also had a pretty late night on Wednesday jamming with P, a very charming young man who’s a student in Boston and is active in the Greek folk music scene. He typically plays laouto, which is a type of Greek lute, (and some lavta, I believe), but he’s also a fantastic lyra player (so we’ve heard) and a very talented violinist, which is what he played at our place on Wednesday night. It was lots of fun, and our housemates G and CL really took to him.

Friday’s concert was at Dionysos, a Greek restaurant and supper club located inside the Radisson Hotel along Memorial Drive in Cambridge. The concert was put on by Dünya and featured a Turkish ensemble that included a clarinet player (who also is a fantastic oud player and happens to be Outiboy’s teacher), a percussionist, an oud player/vocalist, and two violinists. Their music seemed to be a mixture of Ottoman classical and Turkish urban folk music. It was a great show, but it started late, and it was already after 11pm by the time they finished their first set.

Joe was anticipating a busy day on Friday, so we left during the intermission. Joe was disappointed because it meant we were going to miss the Hicaz (Hejaz) set. The concert was organized as a series of fasıls. A fasıl is a suite of songs in the same makam or mode. The first half of the show featured a fasıl in Uşşak (Oussak) and one in Huzzam. Because they were playing Turkish art music, their playing was microtonal; that is, it included the microtones (half flats and half sharps—the notes in between the Western notes) that constitute an integral part of Turkish music, but have gradually disappeared from Greek music.

I worked a half day on Friday (so what am I complaining about?), but had a gazillion chores to do at home. I’ve also been trying to squeeze in some spring cleaning, which we’ve been deferring for too long. Joe and I had planned a little date for ourselves Friday night, since Saturday was our anniversary (that’s another blog post). We went to see A Touch of Spice (Πολίτικη Κουζίνα, 2003) at the West Newton Cinema. The actual name of the film in Greek means “Constantinopolitan cuisine,” though it could also mean “political cuisine” with a slight shifting of the accent. Greeks typically refer to Istanbul not as Istanbul or even Constantinople, but simply as η Πόλη (i PO-li) or “the City,” because for centuries, there was for Greeks only one city, namely Constantinople, which in many ways remains the spiritual capital of the Greek-speaking world, more so than Athens.

I worked a half day on Friday (so what am I complaining about?), but had a gazillion chores to do at home. I’ve also been trying to squeeze in some spring cleaning, which we’ve been deferring for too long. Joe and I had planned a little date for ourselves Friday night, since Saturday was our anniversary (that’s another blog post). We went to see A Touch of Spice (Πολίτικη Κουζίνα, 2003) at the West Newton Cinema. The actual name of the film in Greek means “Constantinopolitan cuisine,” though it could also mean “political cuisine” with a slight shifting of the accent. Greeks typically refer to Istanbul not as Istanbul or even Constantinople, but simply as η Πόλη (i PO-li) or “the City,” because for centuries, there was for Greeks only one city, namely Constantinople, which in many ways remains the spiritual capital of the Greek-speaking world, more so than Athens.

It is the story of a Greek family forced to leave Istanbul in the 1960s. During the turbulent period leading up to the Turkish invasion of Cyprus and the subsequent United Nations partition of the island into its northern (Turkish) and southern (Greek) zones, tensions between Istanbul’s Greek minority and the local Turkish population reached a crisis. Beginning in the mid 1950s and throughout the 1960s many Greeks were forced to leave Istanbul, while others left voluntarily and migrated to Greece or became part of the Greek Diaspora living abroad in the United States, Australia, or Canada.

In spite of the troubled context in which the story is set, the film is primarily about food, as its title suggests. The main protagonist, Fanis, spends much of his free time as a child in his grandfather’s spice shop where he learns about the complex relationship between food and feelings. He learns, for example, that one should use cinnamon in one’s κεφτέδες (meatballs), rather than the more customary cumin, because cumin is strong and it makes people turn inward, whereas cinnamon makes people open up and look each other in the eye.

When Fanis and his parents are forced to leave Istanbul, his grandfather stays behind. Fanis also leaves behind the lovely Saime, his Turkish playmate whose mother Aishe was his mother’s best friend and a frequent visitor to his grandfather’s store. Although they are only children, it is clear that they were destined to be married one day.

One of the more poignant elements of the film is the prejudice that Fanis and his family faced in Greece following their arrival from Istanbul. Although they were ethnically and linguistically Greek, Greeks migrating to Greece from Asia Minor were derisively referred to as “Turks” by their neighbors. Their music and their culture—including their cuisine—was regarded as foreign and oriental. This was as true for Constantinopolitan Greeks who migrated to Greece in the 1950s and 60s as it was for the tens of thousands of impoverished Anatolian Greek refugees that flooded Greece in the 1920s (about whom I have written in my Rembetiko of the Month series).

In Athens, the melancholy Fanis copes with his ξενιτιά (homesickness) and σεβντάς (heartache) by cooking. Though his culinary skills are remarkable for a child his age, his parents ban him from the kitchen when they begin to worry that cooking isn’t a suitable activity for a little boy. Thus begins Fanis’ pursuit of his other great love, astronomy, which his grandfather used to tell him was separated from gastronomy by a single letter.

In Athens, the melancholy Fanis copes with his ξενιτιά (homesickness) and σεβντάς (heartache) by cooking. Though his culinary skills are remarkable for a child his age, his parents ban him from the kitchen when they begin to worry that cooking isn’t a suitable activity for a little boy. Thus begins Fanis’ pursuit of his other great love, astronomy, which his grandfather used to tell him was separated from gastronomy by a single letter.

When Fanis’ aging grandfather falls ill in Istanbul and later dies, Fanis returns to the City and at his grandfather’s funeral is reunited with Saime, grown into a beautiful, seasoned woman with a daughter of her own. Saime is separated from her husband, Mehmet—another of their childhood playmates—who is a military doctor in Ankara. When Saime informs Fanis that it is her daughter Aishe’s birthday, Fanis, still a wonderful cook, prepares the feast. When Saime’s estranged husband shows up uninvited to the birthday party and tastes the meatballs, he notices that they are flavored with cinnamon—the spice that Fanis learned from his grandfather is the one that makes people look each other in the eye. The film leaves us to wonder whether Fanis used cinnamon in order to make Saime fall in love with him or if perhaps he anticipated Mehmet’s arrival—it was his daughter’s birthday, after all—and was trying to patch things up between Saime and her husband because he knew that she was still in love with Mehmet, in spite of their separation.

Joe and I enjoyed the film very much. The food and the music woven into the story of Fanis and his family are familiar to us both and are an intimate part of the way we live. The outsider theme and the way in which Fanis and his family were marginalized for being different resonated with us. Likewise, Istanbul is a city that we both love and have visited twice. Several of the film’s scenes took place in the hamam, which made us long for Istanbul’s hamams of which there are many still in operation.

We ended the evening with dinner at Ten Tables. We were disappointed to learn that it was Shane’s night off, as his charm, knowledge, boyish good looks, and attentiveness have become an important part of why we eat there. Still, the food was delicious as always. We chatted briefly with the chef after our meal, who let us know about some changes that they’ll be making to their summer menu. Overall, they’re a very friendly staff. It has quickly become my favorite place to eat in the city.

We had been planning to do some Pride-related activities on Saturday early in the day, although we did have my cousin’s wedding to attend late Saturday afternoon, which meant we would have to miss the block party. However, the rain that morning made us hesitant to venture downtown. Instead we did some cleaning and errands—very unromantic, since it was our anniversary, after all. I got a call from Dave’s Bike Infirmary in Milton that the bike I had ordered was in. I’ve been riding a 1980 Schwinn since I won it in the Kellogg’s “Stick-up for Breakfast” contest (does anyone remember that?) when I was just a kid.

My mom had convinced me to choose the ten-speed over the child’s bike, even though I had to wait many years before I could fit on the ten-speed, while I would have been able to ride the kid’s bike right away, but would have quickly outgrown it. She was wise, because that bike carried me into adulthood, though it had become a bit of a clunker as of late, falling apart piece by piece. Joe and our housmate G have been on my case for many months to get a new bike, and after some research I finally decided on a Raleigh hybrid (good for city riding as well as distance riding). I was going to get another Schwinn, but the Raleigh model seemed like a better bike in the end. I didn’t end up bringing it home on Saturday, because they’re going to install some accessories, but I’ll pick it up this week.

When the rain didn’t abate, we eventually scrapped our Pride plans altogether and got ready for my cousin’s wedding. The ceremony took place at Saint Vasilios Greek Orthodox Church in Peabody (pictured left, ca. 1918), right outside of Peabody Square, which was badly flooded a few weeks back. My cousin made a lovely bride. After the ceremony, Joe and I went to the Greek coffeehouse/taverna located across the street.

When the rain didn’t abate, we eventually scrapped our Pride plans altogether and got ready for my cousin’s wedding. The ceremony took place at Saint Vasilios Greek Orthodox Church in Peabody (pictured left, ca. 1918), right outside of Peabody Square, which was badly flooded a few weeks back. My cousin made a lovely bride. After the ceremony, Joe and I went to the Greek coffeehouse/taverna located across the street.

Joe was dying for a Greek coffee, and we used the opportunity to inquire about the prospect of our playing music there—though Peabody is a trek from where we live—and they explained that they already have a singer on Saturday nights, but they asked about our ensemble nonetheless. I explained that I played sandouri, that we have a drummer and an accordion player and possibly a violinist, and that Joe plays oud. I was saying all of this in Greek, and when I mentioned the oud, the owner’s wife frowned and said, “Τό ούτι? Τούρκικο είναι,” meaning, “The oud? That’s Turkish.” I thought it ironic that we had just seen A Touch of Spice, which portrayed the way in which many Greeks have often looked at the Greek culture of Asia Minor, which includes the oud, as Turkish.

The reception was lots of fun. In lieu of a Greek band, there was a DJ who played a mixture of house music, disco favorites (what you’d expect to hear at a wedding, minus the Electric Slide and the Macarena, thank God), with a couple of lengthy sets of traditional Greek dance music in between. I was glad because I thought there wouldn’t be any Greek dancing. I like house music as much as the next homo, but it was a Greek wedding after all (well, the bride is half Greek). Almost my whole extended family got up to dance. It was really rather poignant. Many of my mother’s siblings are getting on in years, and it was nice to see them and all my many cousins on the dance floor. Joe and I try to bring the family together every other summer for a big party at our place, but we don’t usually dance. There’s something so human about a folk dancing and line dancing especially—concentric circles of interconnected people celebrating life and expressing their joy in unison. Greeks (and Greek Americans) tend to be very exuberant that way.

It was interesting because in addition to some of the more traditional line dances, the DJ played (probably by request) some of the couples dances that were more common to the islands and Asia Minor. My extended family on my mother’s side traces its roots to Lesbos. I danced an απτάλικος (aptalikos) dance with Joe and then with my cousin Julie and then a ζεϊμπέκικος (zeimbekikos) dance with my mother. My mother is still a great dancer. Most of what I learned about Greek dance I learned from her. They played Απτάλ Χαβασί (Aptal Havası), which was a nice tribute to my maternal grandfather (the bride’s great grandfather), as it was one of his favorites. That’s the one Joe and I danced together.

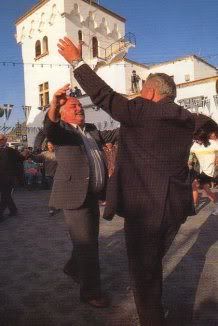

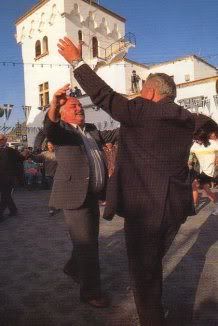

The απτάλικος and the ζεϊμπέκικος (pictured right) were traditionally danced by two men or by a solo male. Once upon a time, women would never have thought of dancing either of these dances. It is also these very dances that would be regarded by mainland Greeks as Turkish and oriental. Again, an odd connection to A Touch of Spice. Speaking of Turkish dances, they also played a couple of τσίφτε τέλλια (belly dances), to which I shook my thang, probably to the horror of my parents. I don’t really feel constrained by traditional notions of gender, and I’m not really all that concerned about embarrassing my parents. Besides, I’m a damn good belly dancer. I think also that if children never do anything to make their parents uncomfortable, then they’re doing something wrong. Progress happens when old ideas and values are challenged.

The απτάλικος and the ζεϊμπέκικος (pictured right) were traditionally danced by two men or by a solo male. Once upon a time, women would never have thought of dancing either of these dances. It is also these very dances that would be regarded by mainland Greeks as Turkish and oriental. Again, an odd connection to A Touch of Spice. Speaking of Turkish dances, they also played a couple of τσίφτε τέλλια (belly dances), to which I shook my thang, probably to the horror of my parents. I don’t really feel constrained by traditional notions of gender, and I’m not really all that concerned about embarrassing my parents. Besides, I’m a damn good belly dancer. I think also that if children never do anything to make their parents uncomfortable, then they’re doing something wrong. Progress happens when old ideas and values are challenged.

We got home very late, but instead of sleeping in Sunday morning, Joe and I were up early and on the road to Lynn to help my parents clear out their basement in anticipation of their move. I also wanted to see my nephews, who weren’t at the wedding. In between loading boxes onto a rented van, Joe and I played with them, mostly with the older one, who’s now 2½ years old and talking quite a bit and a delightful child.

We ended the day attending a work function for Joe. We were both pretty tired, but it ended up being quite a nice affair. The food was great. It was at the home of one of his colleagues who lives out in Wellesley, which couldn’t be more different from our neighborhood. Well, I guess it could be even more different, but our neighborhood ain’t no Wellesley. But we love it anyway.

Thursday night Joe, Mike the drummer, and I played at Café Apollonia. Thursday are normally Joe’s and Mike’s gig, but because we were all heading to a concert later that evening, it was easier for me to come along than have Joe pick me up at home afterwards. I didn’t play sandouri, just spoons and zils. We’d also had a pretty late night on Wednesday jamming with P, a very charming young man who’s a student in Boston and is active in the Greek folk music scene. He typically plays laouto, which is a type of Greek lute, (and some lavta, I believe), but he’s also a fantastic lyra player (so we’ve heard) and a very talented violinist, which is what he played at our place on Wednesday night. It was lots of fun, and our housemates G and CL really took to him.

Friday’s concert was at Dionysos, a Greek restaurant and supper club located inside the Radisson Hotel along Memorial Drive in Cambridge. The concert was put on by Dünya and featured a Turkish ensemble that included a clarinet player (who also is a fantastic oud player and happens to be Outiboy’s teacher), a percussionist, an oud player/vocalist, and two violinists. Their music seemed to be a mixture of Ottoman classical and Turkish urban folk music. It was a great show, but it started late, and it was already after 11pm by the time they finished their first set.

Joe was anticipating a busy day on Friday, so we left during the intermission. Joe was disappointed because it meant we were going to miss the Hicaz (Hejaz) set. The concert was organized as a series of fasıls. A fasıl is a suite of songs in the same makam or mode. The first half of the show featured a fasıl in Uşşak (Oussak) and one in Huzzam. Because they were playing Turkish art music, their playing was microtonal; that is, it included the microtones (half flats and half sharps—the notes in between the Western notes) that constitute an integral part of Turkish music, but have gradually disappeared from Greek music.

I worked a half day on Friday (so what am I complaining about?), but had a gazillion chores to do at home. I’ve also been trying to squeeze in some spring cleaning, which we’ve been deferring for too long. Joe and I had planned a little date for ourselves Friday night, since Saturday was our anniversary (that’s another blog post). We went to see A Touch of Spice (Πολίτικη Κουζίνα, 2003) at the West Newton Cinema. The actual name of the film in Greek means “Constantinopolitan cuisine,” though it could also mean “political cuisine” with a slight shifting of the accent. Greeks typically refer to Istanbul not as Istanbul or even Constantinople, but simply as η Πόλη (i PO-li) or “the City,” because for centuries, there was for Greeks only one city, namely Constantinople, which in many ways remains the spiritual capital of the Greek-speaking world, more so than Athens.

I worked a half day on Friday (so what am I complaining about?), but had a gazillion chores to do at home. I’ve also been trying to squeeze in some spring cleaning, which we’ve been deferring for too long. Joe and I had planned a little date for ourselves Friday night, since Saturday was our anniversary (that’s another blog post). We went to see A Touch of Spice (Πολίτικη Κουζίνα, 2003) at the West Newton Cinema. The actual name of the film in Greek means “Constantinopolitan cuisine,” though it could also mean “political cuisine” with a slight shifting of the accent. Greeks typically refer to Istanbul not as Istanbul or even Constantinople, but simply as η Πόλη (i PO-li) or “the City,” because for centuries, there was for Greeks only one city, namely Constantinople, which in many ways remains the spiritual capital of the Greek-speaking world, more so than Athens.It is the story of a Greek family forced to leave Istanbul in the 1960s. During the turbulent period leading up to the Turkish invasion of Cyprus and the subsequent United Nations partition of the island into its northern (Turkish) and southern (Greek) zones, tensions between Istanbul’s Greek minority and the local Turkish population reached a crisis. Beginning in the mid 1950s and throughout the 1960s many Greeks were forced to leave Istanbul, while others left voluntarily and migrated to Greece or became part of the Greek Diaspora living abroad in the United States, Australia, or Canada.

In spite of the troubled context in which the story is set, the film is primarily about food, as its title suggests. The main protagonist, Fanis, spends much of his free time as a child in his grandfather’s spice shop where he learns about the complex relationship between food and feelings. He learns, for example, that one should use cinnamon in one’s κεφτέδες (meatballs), rather than the more customary cumin, because cumin is strong and it makes people turn inward, whereas cinnamon makes people open up and look each other in the eye.

When Fanis and his parents are forced to leave Istanbul, his grandfather stays behind. Fanis also leaves behind the lovely Saime, his Turkish playmate whose mother Aishe was his mother’s best friend and a frequent visitor to his grandfather’s store. Although they are only children, it is clear that they were destined to be married one day.

One of the more poignant elements of the film is the prejudice that Fanis and his family faced in Greece following their arrival from Istanbul. Although they were ethnically and linguistically Greek, Greeks migrating to Greece from Asia Minor were derisively referred to as “Turks” by their neighbors. Their music and their culture—including their cuisine—was regarded as foreign and oriental. This was as true for Constantinopolitan Greeks who migrated to Greece in the 1950s and 60s as it was for the tens of thousands of impoverished Anatolian Greek refugees that flooded Greece in the 1920s (about whom I have written in my Rembetiko of the Month series).

In Athens, the melancholy Fanis copes with his ξενιτιά (homesickness) and σεβντάς (heartache) by cooking. Though his culinary skills are remarkable for a child his age, his parents ban him from the kitchen when they begin to worry that cooking isn’t a suitable activity for a little boy. Thus begins Fanis’ pursuit of his other great love, astronomy, which his grandfather used to tell him was separated from gastronomy by a single letter.

In Athens, the melancholy Fanis copes with his ξενιτιά (homesickness) and σεβντάς (heartache) by cooking. Though his culinary skills are remarkable for a child his age, his parents ban him from the kitchen when they begin to worry that cooking isn’t a suitable activity for a little boy. Thus begins Fanis’ pursuit of his other great love, astronomy, which his grandfather used to tell him was separated from gastronomy by a single letter.When Fanis’ aging grandfather falls ill in Istanbul and later dies, Fanis returns to the City and at his grandfather’s funeral is reunited with Saime, grown into a beautiful, seasoned woman with a daughter of her own. Saime is separated from her husband, Mehmet—another of their childhood playmates—who is a military doctor in Ankara. When Saime informs Fanis that it is her daughter Aishe’s birthday, Fanis, still a wonderful cook, prepares the feast. When Saime’s estranged husband shows up uninvited to the birthday party and tastes the meatballs, he notices that they are flavored with cinnamon—the spice that Fanis learned from his grandfather is the one that makes people look each other in the eye. The film leaves us to wonder whether Fanis used cinnamon in order to make Saime fall in love with him or if perhaps he anticipated Mehmet’s arrival—it was his daughter’s birthday, after all—and was trying to patch things up between Saime and her husband because he knew that she was still in love with Mehmet, in spite of their separation.

Joe and I enjoyed the film very much. The food and the music woven into the story of Fanis and his family are familiar to us both and are an intimate part of the way we live. The outsider theme and the way in which Fanis and his family were marginalized for being different resonated with us. Likewise, Istanbul is a city that we both love and have visited twice. Several of the film’s scenes took place in the hamam, which made us long for Istanbul’s hamams of which there are many still in operation.

We ended the evening with dinner at Ten Tables. We were disappointed to learn that it was Shane’s night off, as his charm, knowledge, boyish good looks, and attentiveness have become an important part of why we eat there. Still, the food was delicious as always. We chatted briefly with the chef after our meal, who let us know about some changes that they’ll be making to their summer menu. Overall, they’re a very friendly staff. It has quickly become my favorite place to eat in the city.

We had been planning to do some Pride-related activities on Saturday early in the day, although we did have my cousin’s wedding to attend late Saturday afternoon, which meant we would have to miss the block party. However, the rain that morning made us hesitant to venture downtown. Instead we did some cleaning and errands—very unromantic, since it was our anniversary, after all. I got a call from Dave’s Bike Infirmary in Milton that the bike I had ordered was in. I’ve been riding a 1980 Schwinn since I won it in the Kellogg’s “Stick-up for Breakfast” contest (does anyone remember that?) when I was just a kid.

My mom had convinced me to choose the ten-speed over the child’s bike, even though I had to wait many years before I could fit on the ten-speed, while I would have been able to ride the kid’s bike right away, but would have quickly outgrown it. She was wise, because that bike carried me into adulthood, though it had become a bit of a clunker as of late, falling apart piece by piece. Joe and our housmate G have been on my case for many months to get a new bike, and after some research I finally decided on a Raleigh hybrid (good for city riding as well as distance riding). I was going to get another Schwinn, but the Raleigh model seemed like a better bike in the end. I didn’t end up bringing it home on Saturday, because they’re going to install some accessories, but I’ll pick it up this week.

When the rain didn’t abate, we eventually scrapped our Pride plans altogether and got ready for my cousin’s wedding. The ceremony took place at Saint Vasilios Greek Orthodox Church in Peabody (pictured left, ca. 1918), right outside of Peabody Square, which was badly flooded a few weeks back. My cousin made a lovely bride. After the ceremony, Joe and I went to the Greek coffeehouse/taverna located across the street.

When the rain didn’t abate, we eventually scrapped our Pride plans altogether and got ready for my cousin’s wedding. The ceremony took place at Saint Vasilios Greek Orthodox Church in Peabody (pictured left, ca. 1918), right outside of Peabody Square, which was badly flooded a few weeks back. My cousin made a lovely bride. After the ceremony, Joe and I went to the Greek coffeehouse/taverna located across the street. Joe was dying for a Greek coffee, and we used the opportunity to inquire about the prospect of our playing music there—though Peabody is a trek from where we live—and they explained that they already have a singer on Saturday nights, but they asked about our ensemble nonetheless. I explained that I played sandouri, that we have a drummer and an accordion player and possibly a violinist, and that Joe plays oud. I was saying all of this in Greek, and when I mentioned the oud, the owner’s wife frowned and said, “Τό ούτι? Τούρκικο είναι,” meaning, “The oud? That’s Turkish.” I thought it ironic that we had just seen A Touch of Spice, which portrayed the way in which many Greeks have often looked at the Greek culture of Asia Minor, which includes the oud, as Turkish.

The reception was lots of fun. In lieu of a Greek band, there was a DJ who played a mixture of house music, disco favorites (what you’d expect to hear at a wedding, minus the Electric Slide and the Macarena, thank God), with a couple of lengthy sets of traditional Greek dance music in between. I was glad because I thought there wouldn’t be any Greek dancing. I like house music as much as the next homo, but it was a Greek wedding after all (well, the bride is half Greek). Almost my whole extended family got up to dance. It was really rather poignant. Many of my mother’s siblings are getting on in years, and it was nice to see them and all my many cousins on the dance floor. Joe and I try to bring the family together every other summer for a big party at our place, but we don’t usually dance. There’s something so human about a folk dancing and line dancing especially—concentric circles of interconnected people celebrating life and expressing their joy in unison. Greeks (and Greek Americans) tend to be very exuberant that way.

It was interesting because in addition to some of the more traditional line dances, the DJ played (probably by request) some of the couples dances that were more common to the islands and Asia Minor. My extended family on my mother’s side traces its roots to Lesbos. I danced an απτάλικος (aptalikos) dance with Joe and then with my cousin Julie and then a ζεϊμπέκικος (zeimbekikos) dance with my mother. My mother is still a great dancer. Most of what I learned about Greek dance I learned from her. They played Απτάλ Χαβασί (Aptal Havası), which was a nice tribute to my maternal grandfather (the bride’s great grandfather), as it was one of his favorites. That’s the one Joe and I danced together.

The απτάλικος and the ζεϊμπέκικος (pictured right) were traditionally danced by two men or by a solo male. Once upon a time, women would never have thought of dancing either of these dances. It is also these very dances that would be regarded by mainland Greeks as Turkish and oriental. Again, an odd connection to A Touch of Spice. Speaking of Turkish dances, they also played a couple of τσίφτε τέλλια (belly dances), to which I shook my thang, probably to the horror of my parents. I don’t really feel constrained by traditional notions of gender, and I’m not really all that concerned about embarrassing my parents. Besides, I’m a damn good belly dancer. I think also that if children never do anything to make their parents uncomfortable, then they’re doing something wrong. Progress happens when old ideas and values are challenged.

The απτάλικος and the ζεϊμπέκικος (pictured right) were traditionally danced by two men or by a solo male. Once upon a time, women would never have thought of dancing either of these dances. It is also these very dances that would be regarded by mainland Greeks as Turkish and oriental. Again, an odd connection to A Touch of Spice. Speaking of Turkish dances, they also played a couple of τσίφτε τέλλια (belly dances), to which I shook my thang, probably to the horror of my parents. I don’t really feel constrained by traditional notions of gender, and I’m not really all that concerned about embarrassing my parents. Besides, I’m a damn good belly dancer. I think also that if children never do anything to make their parents uncomfortable, then they’re doing something wrong. Progress happens when old ideas and values are challenged.We got home very late, but instead of sleeping in Sunday morning, Joe and I were up early and on the road to Lynn to help my parents clear out their basement in anticipation of their move. I also wanted to see my nephews, who weren’t at the wedding. In between loading boxes onto a rented van, Joe and I played with them, mostly with the older one, who’s now 2½ years old and talking quite a bit and a delightful child.

We ended the day attending a work function for Joe. We were both pretty tired, but it ended up being quite a nice affair. The food was great. It was at the home of one of his colleagues who lives out in Wellesley, which couldn’t be more different from our neighborhood. Well, I guess it could be even more different, but our neighborhood ain’t no Wellesley. But we love it anyway.

4 Comments:

Congratulations on another anniversary!

thanks, treeboy :)

Intersting blog.

I came accross it whilst trying to find out what's written about aptalikos beat . Really like the way the old rebetes used it almost exlusivley inplace of the Zeibekiko.

You remind me of my youth. I 'm from a musical family , my father was a pioneer in bringing live Greek music to all over Britain.

Things are more developed in USA .

Greek music has declined in popularity in London , I don't play much in restaurants nowadays .

Good luck with your gigs I love the sound of the sandouri, don't know anyone here who plays it ,it was Zorba's favourite . post a tune if that's possible and finally how do you type in Greek that's always a mystery to me? guess I'm too old for these computers .

Yia kai hara sou!

Good blog , keep up the sandouri

post us a tune if that is possible

Post a Comment

<< Home