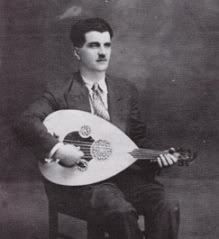

As a follow-up to my last

Rembetiko of the Month post, I’d like to say a few things in response to Matthew and others who took the time to register their objections to what I wrote. I don’t always devote an entire separate post to issues that have been raised in comments, but have no problem doing so when I feel it is warranted.

First of all, I want to clarify that my allusion to the events that took place in Smyrna in September 1922 was not because I feel that the song featured in my post addresses those events or was written about those events. If you read that post, you’ll recall that I acknowledged that the song is understood as being addressed to a child whose mother died during childbirth.

I brought up the destruction of Smyrna because that’s what I think of when I hear Asikis’ haunting lullaby. To say that the song makes me think of the loss of life that took place in Smyrna in September 1922 is a factual statement, quite different than my saying that the song is

about Smyrna. I don’t feel the need to offer an apology for that, for such is the evocative power of art.

The mind moves in leaps and bounds, making connections and associations that are often unpredictable. Only a small minority of conservative-minded people would argue that one should only think and feel those things that the artist intended. We don’t always (or even often) know precisely what an artist intended and even if we did, how could we (and why would we) train our minds to think and feel only those things?

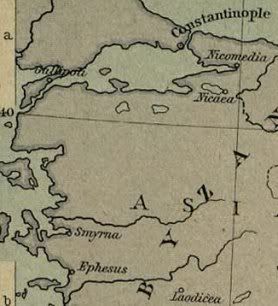

Nor do I think it inappropriate to talk about unpleasant historical events in relation to art, which cannot be divorced from its historic context. Rembetika, for example, cannot be understood apart from the tragic events that unfolded in Asia Minor and Greece during the first decades of the twentieth century.

More importantly, I stand by my statements about the massacre of Greek and Armenian civilians by Atatürk’s army (under the command of Nureddin Pasha) in September 1922. Others may dismiss these events as myths and lies, but I cannot and will not. In writing about them, moreover, my concern is not with their offensiveness, but with their veracity.

I believe the accounts of atrocities committed by the Turkish army in Smyrna to be true. I assess their veracity using the same criteria used by historians in writing about any past event. One such criterion is whether or not one person’s version of the story can be corroborated by other independent sources. Greek and Armenian eyewitnesses who survived the massacre along with American diplomats and missionaries and other foreign observers all attest to the murder of Greek and Armenian civilians in Smyrna, with news dispatches from the destroyed city estimating the number of dead at over 100,000.

Richard Clogg in

A Concise History of Modern Greece puts the number of Christian civilians murdered at Smyrna considerably lower at 20,000 to 30,000. The precise number will probably never be known. It should be noted that these events, along with the larger persecution of the Ottoman Empire’s Greek and Armenian subjects that took place between 1914 and 1922, are contested by the Turkish government, but that is not a compelling reason for me to conclude that they did not take place.

Moreover, to justify these atrocities on the grounds that the Greek army had invaded and occupied the west coast of Asia Minor beginning in 1919 constitutes moral myopia. The Greek and Armenian civilian populations of Asia Minor were not subjects of Greece. They were Ottoman subjects and they were non-combatants. The slaughter of innocent civilians—even when they share the same ethnicity with enemy soldiers—must be distinguished from slaughter on the battlefield, and the correct response is not to defend it, but to condemn it. That is precisely what I have done in the case of the

War on Terror, for example.

It is curious to me that Matthew would feel that my acknowledgement that “atrocities were committed on both sides” was not strong enough, as though making such an acknowledgement were itself insignificant. If that is the case, why is it so difficult for

some to acknowledge that Atatürk’s army committed atrocities?

I admitted in my post—and have never denied—that the Greek army committed atrocities against the Turkish civilian population during their occupation of Asia Minor between 1919 and 1922. It is important to point out, however, that the Greek High Commissioner, Aristides Stergiadis, who was responsible for overseeing the Greek occupation of Smyrna and the surrounding area, is widely recognized as having been harsh and swift in his discipline of Greek soldiers who abused Turkish civilians.

Nonetheless, during the course of the occupation (especially during the landing of the Greek army in Smyrna in 1919 and then again during the their hasty and disorganized retreat in the summer of 1922) atrocities occurred, but never on the scale of the massacres that took place against the Greeks and Armenians along the Aegean and Black Sea coasts, in the Anatolian heartland, and in the eastern provinces. I do not say this to minimize the deaths of Turkish civilians, but simply to point out that they did not occur on the same scale as the mass killings of Greeks and Armenians.

The tragic events that took place at Smyrna in September 1922 were but one episode in a series of violent acts committed against the Empire’s civilian populations (the Armenian genocide being part of this) between 1914 and 1922. In spite of the fact that these events are well documented, many Turkish politicians have demonstrated their unwillingness to acknowledge the deliberate killing of civilians by the Turkish armed forces during the Ottoman Empire’s final decades.

Not only have these crimes not been acknowledged, but the Turkish government went so far as to

ban an academic conference on the subject last year. Rather than criticizing those who openly acknowledge that atrocities were committed on both sides, perhaps Matthew should be criticizing those who refuse even to acknowledge that atrocities were committed at all.

It seems to me that in both Matthew’s and Sotiris’ (another who commented on my Rembetiko post) comments, I am being condemned for not saying things that they feel I should have said, but I am also being accused of saying things that I did not actually say.

Allow me to point out that my post was not an attempt to provide either a comprehensive list of the atrocities committed by the Greeks and Turks against one another or a full blown analysis of the Greco-Turkish conflict following the First World War. I’d like to remind them that my last Rembetiko of the Month was a blog post, not a doctoral thesis. Nor was it intended to address the Orthodox religion or Cyprus and the suffering (on both sides) that occurred there.

Moreover, just because I have not addressed a particular topic does not give anyone license to project an opinion onto me (simply to justify their rant). That is presumptuous, since I am the most qualified to speak about what I do or do not believe. I am not so easily pigeonholed.

I think that Sotiris and Matthew also need to be reminded that not every Greek (or Greek American in my case) who talks about Smyrna and the atrocities committed by Atatürk’s army is a rabid Greek nationalist eager to defend Greece and dehumanize the Turkish people. As for me, I can hardly be considered an apologist for Greece. Many of my Rembetiko of the Month posts describe the prejudice encountered by Greek refugees from Asia Minor following their arrival in Greece in the 1920s, and I have written several posts criticizing both

Greece and

Cyprus for their discriminatory treatment of sexual minorities. Scroll through the archives and you’ll find them.

I have avoided making sweeping generalizations that condemn or “pothole” (Matthew’s term) an entire nation or race. I have never in the past nor will I in the future refer to Turks as barbarians, a view that Sotiris was taught as a child and seems eager to attribute to me, a fellow Greek of the Diaspora. While Sotiris has clearly come across Greeks who deny that the Turkish people constitute a distinct ethnic group with their own culture and history, I have made no such claims on my blog, nor will I.

However, one must be allowed—in fact, has a moral and ethical obligation—to condemn atrocities, both past and present, without being accused of racism or ethnocentrism, lest the world’s armies be granted the license to act with impunity against civilian populations. If atrocities disappear from our collective memory, we are more likely to repeat them.

Recommended Reading:

Ambassador Morgenthau’s Story by Henry Morgenthau

The Blight of Asia by George Horton

Not Even My Name by Thea Halo

A Concise History of Greece by Richard Clogg

From Empire to Republic: Turkish Nationalism and the Armenian Genocide by Taner Akçam

Smyrna 1922: The Destruction of a City by Marjorie Housepian Dobkin

Ionian Vision: Greece in Asia Minor, 1919-1922 by Michael Llewellyn Smith

Farewell Anatolia by Dido Sotiriou

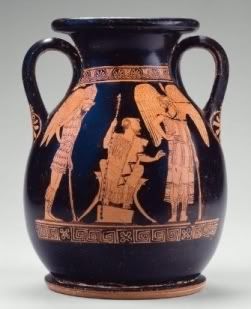

While I believe that the looting of art and the illegal trafficking of antiquities are to be condemned, I think hypocrisy is also to be condemned. This week, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts transferred to the Italian Ministry of Culture thirteen objects from its collection that the Italian government determined to have been looted and sold illegally to the MFA. A similar transfer occurred in February of this year when New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art returned twenty objects, including the 2500-year old Euphronios krater, to Italy.

While I believe that the looting of art and the illegal trafficking of antiquities are to be condemned, I think hypocrisy is also to be condemned. This week, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts transferred to the Italian Ministry of Culture thirteen objects from its collection that the Italian government determined to have been looted and sold illegally to the MFA. A similar transfer occurred in February of this year when New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art returned twenty objects, including the 2500-year old Euphronios krater, to Italy.