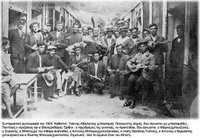

Some aficionados of Rembetika who have stumbled upon my blog might be wondering why this month I’m posting another

Smyrnaïc song (Σμυρνέϊκο) for what was supposed to be a monthly series featuring Rembetika. I often find that an artificial line is drawn between the two (i.e. Rembetika and Smyrnaïka). However, in reality not only are they closely related, but Smyrnaïka is rightly considered one of Rembetika’s two Schools, the other being the Piraeus School.

Smyrnaïka refers to the style of music that was heard in the musical cafés (the “Café Aman” establishments) of

Smyrna before it was destroyed in 1922. As a style, however, its impact was much broader than simply Smyrna, and included much of the western shore of Asia Minor and the neighboring islands (

Lesbos, for example). It featured different combinations of instruments, the most common being the

sandouri, the violin, the oud, the kanun (zither), the guitar, the mandolin, and the piano. Though decidedly oriental in style, Western influences could also be felt.

The Piraeus School, on the other hand, was a tradition that really blossomed in the slums and shanty towns of Athens and Piraeus following the Asia Minor catastrophe of 1922 and the arrival in Greece of more than a million Anatolian refugees. Although Smyrnaïka could be heard among the refugees, the Piraeus School is often what is thought of when Rembetika is mentioned. This might be because the instrument of choice for musicians of the Piraeus School was the bouzouki (and to some extent the baglamas), which is what most people think of when they think of Greek music.

The music of the Piraeus School was less associated with the bourgeois atmosphere of the Café Aman than it was with the hash dens, drinking establishments, and the dark underworld that characterized life in the refugee shanty towns. If Smyrnaïka was the music of Asia Minor’s Greek merchant class, the Piraeus School was the music of Greece’s urban underclass.

Among the Greeks of “Old Greece” (i.e. the areas that constituted the Kingdom of Greece prior to Balkan Wars of 1912-13 and the subsequent acquisition of the northern territories and the Eastern Aegean islands), both Smyrnaïka and the Piraeus School were for the most part closely associated with the Anatolian refugees that flooded Greece after the defeat of the Greek army by Atatürk’s nationalist forces in 1922 and the subsequent expulsion of Turkey’s Greek population. Both Schools were initially regarded by many mainland Greeks as too foreign, too oriental—too Turkish. In time, however, both would become wildly popular both in Greece and among the Greeks of the Diaspora (in America, for example). I would argue, moreover, that both Schools left their mark on the popular music (λαϊκά) that emerged in Greece in the 1950s and 60s and is still being produced today.

While I will eventually get around to posting songs of the Piraeus School, my own preference is for Smyrnaïka. This month’s decidedly Smyrnaïc song, Καδιφής (Kadifis), was recorded in Athens in 1930 by Roza Eskenazi, Lambros Leondaridis on lyra, Agapios Tomboulis on oud, and Lambros Savaïdis on kanun. I was actually planning on posting a song by Rita Abadzi, another famous Rembetissa. Abadzi was originally from Smyrna and thus recorded many songs in the Smyrnaïc style, and on most days, I think I prefer her to Eskenazi.

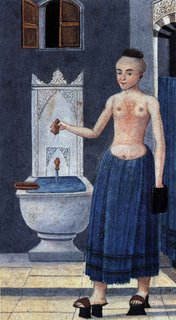

At the last minute, however, I chose Καδιφής because the melody is roughly the same as the Turkish melody that would have accompanied the lyrics featured in my

previous post about the talak and his silk scrubbing-mitten. It was not uncommon for Rembetika tunes to have both a Greek and a Turkish (and sometimes a Ladino) version. This is true not only for Rembetika, but for other genres of Greek music as well, but that’s another story.

Though the Greek and the Turkish melodies were practically the same, Eskenazi sings a different set of lyrics entirely. There are several Greek versions of Kadife, but none, to my knowledge, are about a talak. If anybody knows of one, please let me know.

It is worth noting that, although the vocal portion of the song is in a typical belly-dance rhythm, having 4 beats per measure, the instrumental bridges between the verses contain several measures with 4 beats plus a single measure containing

5 beats, just prior to the verse. Outiboy pointed this out to me, and at first I didn't believe him.

Click here to listen.Δεν μου λέτε χθες το βράδυ ο θυμός σου τί ήτανε;

δυό σου φίλοι μ’ανταμώσαν καί γιά σένα μού’πανε.

Δεν μπορώ νά καταλάβω τα δικά σου μυστικά,

στους γιατρούς θε νά με ρίξεις νά πεθάνω φθισικιά.

Τα ματάκια σου πουλί μου χαμηλώνεις δεν μου λές,

σαν γυρίζουν καί με’ιδούνε στην καρδιά με σφάζουνε.

Έλα νά αλλάξουμε καρδιές νά πάρεις τη δική μου

νά δείς πώς βασανίζεται γιά σένα το κορμί μου.

Why don’t you tell me why you were so angry the other night?

I ran into two of your friends, and they gave me an earful.

I don’t understand your secrets;

You want to send me off to the doctors to die of tuberculosis.

Your eyes, my little bird, why do you lower them?

You turn them upon me, and they break my heart.

Come, let’s exchange hearts, you take mine;

That way you’ll see how my body longs for you.

Like the Turkish Kadife, this is a love song, but it’s a decidedly more painful one. I find the lyrics, moreover, evocative of the Third Act of Puccini’s

La Bohème, as Rodolfo and Mimi are on the verge of splitting up. Rodolfo tells his friends Marcello and Colin that he has become tired of Mimi’s coquettish ways. He and Mimi fight constantly as a result of his apparent jealousy. In reality, however, he can’t bear to see her suffering in his cold flat as her tuberculosis worsens, so he uses his jealousy as a pretense for sending her away.

Rodolfo m’ama e mi fugge.

Rodolfo si strugge per gelosia.

Un passo, un ditto, un vezzo,

Un fior lo mettono in sospetto…

Onde corrucci ed ire.

Talor la notte fingo di dormire

E in me lo sento fiso

Spiarmi I sogni in viso.

Mi grida ad ogni instante:

Non fai per me, ti prendi

Un altro amante,

Non fai per me. Ahimé!

Rodolfo, he loves me,

But he flees from me, torn

by jealousy. A glance, a gesturre,

a smile, a flower arouses

his suspicions, then anger, rage…

Sometimes at night I pretend

To sleep, and I feel his eyes

trying to spy on my dreams.

He shouts at me all the time:

“You’re not for me,

Find another!

You’re not for me!”

Invan, invan nascondo

La mia vera tortura.

Amo Mimì sovra ogni cosa

Al mondo. L’amo! Ma ho paura.

Mimì è tanto malata!

Ogni dì più declina.

La povera piccina

È condannata…

La mia stana è una tana

Squallida. Il fuoco è spento.

V’entra e l’aggira il vento.

Di tramontana.

Essa canta e sorride

E il rimorso m’assale.

Me, cagion del fatale

Mai che l’uccide.

My room is like a squalid cave.

The fire has gone out.

The wind, the winter wind

howls through it.

She laughs and sings;

I’m wracked by guilt.

I fear I’m the cause of the illness

that’s killing her.

La Bohème would surely have played in the opera houses of Smyrna and Constantinople. I wouldn’t go so far as to assert a definite link between it and the lyrics sung by Eskenazi in the 1930 version of Καδιφής, for such could not be proven. My point is only that it is possible that listeners back then who were familiar with

La Bohème might have been reminded of the ill-fated love affair between Mimi and Rodolfo when they heard Eskenazi’s Καδιφής.

Recommended listening:

The Rebetiko Song in America 1920-1940

Made dinner on Saturday for our housemate D and our friend F for their birthdays, which were both several weeks ago. Joe made manicotti (from scratch) and a nice big pot of gravy—for all you non-Italians, that’s tomato sauce with meat. It’s taken me quite a while to start referring to tomato sauce as gravy. But it’s only gravy if it has meat in it. In Joe’s case, his gravy is full of pork ribs and sausage. Meatless tomato sauce isn’t gravy, but marinara.

Made dinner on Saturday for our housemate D and our friend F for their birthdays, which were both several weeks ago. Joe made manicotti (from scratch) and a nice big pot of gravy—for all you non-Italians, that’s tomato sauce with meat. It’s taken me quite a while to start referring to tomato sauce as gravy. But it’s only gravy if it has meat in it. In Joe’s case, his gravy is full of pork ribs and sausage. Meatless tomato sauce isn’t gravy, but marinara.  I called Tutto Italiano (1893 River Street, Hyde Park) a few days in advance to order the ingredients so I could just breeze in Saturday morning and pick up everything. They are very popular and are pretty much busy from the moment they open on Saturday and I really hate having to wait in line. However, even having called ahead so as to avoid a long wait, I still felt rushed Saturday as evinced by my having put my sweater on inside-out. Joe found this very amusing and thought it would be cute to take a picture of the back of my neck showing that I still haven’t learned to dress myself. I must have still been rushing around that evening, my rapid movements causing the only photo of me to come out quite blurry. I liked it.

I called Tutto Italiano (1893 River Street, Hyde Park) a few days in advance to order the ingredients so I could just breeze in Saturday morning and pick up everything. They are very popular and are pretty much busy from the moment they open on Saturday and I really hate having to wait in line. However, even having called ahead so as to avoid a long wait, I still felt rushed Saturday as evinced by my having put my sweater on inside-out. Joe found this very amusing and thought it would be cute to take a picture of the back of my neck showing that I still haven’t learned to dress myself. I must have still been rushing around that evening, my rapid movements causing the only photo of me to come out quite blurry. I liked it. Mike the drummer was also present. He shaved his beard (as he had warned me he was going to do) even though I told him that I would likely find him irresistible clean-shaven. Indeed, when I answered the door and beheld his boyish beardless face underneath his lovely mop of red hair, I had to resist the impulse to plant one on him on the spot. He’s quite adorable and he now knows that I think so, but he’s sweet and indulges me in my crush. Liberated straight guys are so cool. He also brought a cheesecake that he made himself, which was delicious.

Mike the drummer was also present. He shaved his beard (as he had warned me he was going to do) even though I told him that I would likely find him irresistible clean-shaven. Indeed, when I answered the door and beheld his boyish beardless face underneath his lovely mop of red hair, I had to resist the impulse to plant one on him on the spot. He’s quite adorable and he now knows that I think so, but he’s sweet and indulges me in my crush. Liberated straight guys are so cool. He also brought a cheesecake that he made himself, which was delicious.