Baptize This

I composed this post a couple of days ago, but I’ve decided to dedicate it to Lonnie Latham, senior pastor at Oklahoma’s South Tulsa Baptist Church and an executive committee member of the Southern Baptist Convention, who was arrested this past Tuesday on a lewdness charge for propositioning a plainclothes policeman outside a hotel. Latham has campaigned vigorously against same-sex marriage and has condemned homosexuality as a “sinful, destructive lifestyle.” Lonnie, this one’s for you.

I composed this post a couple of days ago, but I’ve decided to dedicate it to Lonnie Latham, senior pastor at Oklahoma’s South Tulsa Baptist Church and an executive committee member of the Southern Baptist Convention, who was arrested this past Tuesday on a lewdness charge for propositioning a plainclothes policeman outside a hotel. Latham has campaigned vigorously against same-sex marriage and has condemned homosexuality as a “sinful, destructive lifestyle.” Lonnie, this one’s for you........

OK, not all of my posts will be dictated by Orthodox feastdays, but I really couldn’t resist this one. Today (January 7) is the feastday of Saint John the Baptist. If you know a Greek John (Yannis), make sure you wish him Χρόνια Πολλά (Hrónia Pollá)!

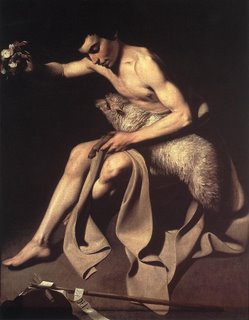

In Byzantine iconography, John the Baptist is portrayed as an emaciated and unkempt figure—not terribly attractive. In the West as well, John was not typically eroticized in the way that Saint Sebastian was. Beginning with the Renaissance, however, there were a handful of artists, Caravaggio chief amongst them, that began to portray John in a more erotic fashion, not as a man physically wasted in the manner of the Greeks, but as a robust, handsome, and nearly naked youth, the very embodiment of young male beauty.

In these works, John is less a starving ascetic than a young Greek god, almost Bacchic in appearance (See daVinci’s St. John in the Wilderness, below). In this way, such works reference the classical ideal of male beauty at least as much as they do the Christian Gospels. Moreover, because John is wild, untamed, unwashed, often set in the wilderness—beyond the boundaries of civilization—he is the perfect image of a raw and potent and barely concealed sexuality. To be sure, such images of John never predominated; but those that were created celebrated the idealized male form as well as any work from the same period.

In these works, John is less a starving ascetic than a young Greek god, almost Bacchic in appearance (See daVinci’s St. John in the Wilderness, below). In this way, such works reference the classical ideal of male beauty at least as much as they do the Christian Gospels. Moreover, because John is wild, untamed, unwashed, often set in the wilderness—beyond the boundaries of civilization—he is the perfect image of a raw and potent and barely concealed sexuality. To be sure, such images of John never predominated; but those that were created celebrated the idealized male form as well as any work from the same period.Certainly Oscar Wilde was aware of this and picked up on it. In Salomé (1893/4), he paints a literary portrait of John the Baptist as an object of desire that inspires lust and passionate longing in the young princess Salomé, who is infatuated with John and captivated by his beauty. John is her fantasy, and her interest in him is wholly erotic:

“I am amorous of thy body…

“I am amorous of thy body…Suffer me to touch thy body…

Suffer me to touch thy hair…

Suffer me to kiss thy mouth…”

After she has given the order for John’s severed head to be brought to her on a silver charger (in this context, because he has spurned her advances), she continues to long for him:

“But thou wert beautiful! Thy body was a column of ivory set upon feet of silver. It was a garden full of doves and lilies of silver. It was a tower of silver decked with shields of ivory. There was nothing in the world so white as thy body. There was nothing in the world so black as thy hair. In the whole world there was nothing so red as thy mouth…I am athirst for thy beauty; I am hungry for thy body… I was chaste, and thou didst fill my veins with fire.”

In the character of Salomé, Wilde is free to give voice to the lust that the Baptist’s body inspires. Surely those communities who viewed these paintings in their original contexts were aroused by what they saw, just as those who view these works today continue to cast libidinous glances in John’s direction and indulge their voyeurism by gazing upon his attractive and exposed body.

I would also argue that these images, in which John is not dressed but merely draped—barely covered, in fact—are suggestive of another figure from the Gospels. In the Gospel of Mark, we are told of a “certain young man, having a linen cloth cast about his naked body,” (Mark 14:51-52) who was following Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane on the night he was arrested. We are told nothing else about him, other than that when Jesus was arrested, the young man fled naked after the soldiers grabbed his garment. While I think it would be a stretch to say that the artists of the works pictured here were themselves inspired by the nude youth in the Garden of Gethsemane or intended their viewers to make any such connection, I do feel that from the viewer’s perspective, anyone familiar with this enigmatic figure from Mark’s Gospel cannot help but be reminded of him when viewing such images of the nearly nude Baptist as are shown here.

I would also argue that these images, in which John is not dressed but merely draped—barely covered, in fact—are suggestive of another figure from the Gospels. In the Gospel of Mark, we are told of a “certain young man, having a linen cloth cast about his naked body,” (Mark 14:51-52) who was following Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane on the night he was arrested. We are told nothing else about him, other than that when Jesus was arrested, the young man fled naked after the soldiers grabbed his garment. While I think it would be a stretch to say that the artists of the works pictured here were themselves inspired by the nude youth in the Garden of Gethsemane or intended their viewers to make any such connection, I do feel that from the viewer’s perspective, anyone familiar with this enigmatic figure from Mark’s Gospel cannot help but be reminded of him when viewing such images of the nearly nude Baptist as are shown here.

On a concluding note, I find it interesting that the Greeks have a separate feastday for John the Baptist’s beheading, which is commemorated August 29.

A few more (the last one being my personal favorite):

A note on the images:

From top to bottom, Guido Reni’s (1575-1642) St. John the Baptist in the Wilderness (1636/7, oil on canvas, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London); Caravaggio’s (c. 1571-1610) St. John the Baptist/Youth with Ram (1600, oil on canvas, Musei Capitolini, Rome); Caravaggio’s St. John the Baptist (oil on canvas, Öffentliche Kunstsammlung, Basle); Caravaggio’s, St. John the Baptist (1603-04, oil on canvas, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Rome); Agnolo Bronzino’s (1503-1572) St. John the Baptist (1550-55, oil on wood, Galleria Borghese, Rome); Nicolas Régnier’s (1590-1667) St. John the Baptist (1610s, oil on canvas, The Hermitage, St. Petersburg); Baciccio’s (1639-1709) St. John the Baptist (c. 1676, oil on canvas, City of Manchester Art Gallery, Manchester); Leonardo da Vinci’s (1452-1519) St. John in the Wilderness/Bacchus (1510-15, oil on panel transferred to canvas, Musée du Louvre, Paris); Bartolomé González y Serrano’s (1564-1627), St. John the Baptist (1621, oil on canvas, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest).

5 Comments:

Richard Strauss made a shocking (for 1906) opera from Wilde's "Salome" in which John is assigned to the virile baritone voice with music as sensuous and glittering as a Guystave Klimt painting.

I like the first one the best, is that Guido Reni’s (1575-1642) St. John the Baptist in the Wilderness (1636/7, oil on canvas, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London?

Funny stuff about Lonnie Latham. Oh, funny stuff indeed.

jjd,

what's your real name?

yup, the very top image is reni's st. john the baptist in the wilderness.

Is it just me, or is there the barely discernible shadow of "an excited staff" in Caravaggio’s St. John the Baptist/Youth with Ram (second from the top of the post)? I think Caravaggio was playing with a little sfumatura eye trickery :)

interesting remarks.

true that since Renaissance John depiction is more and more erotic, and in the same time the image of Salome begins to be more and more of seductive. she no longer looks like this Innocent girl, dancing "innocently" at the feast of Herod's, but a full young women voluptuous, with a certain look on her face, while mostly holding John's head between her hands....

Post a Comment

<< Home